In 2009, Brian Eno – music inventor, record producer and acclaimed visual artist – was invited to Sydney to curate a project called Luminous, part of Vivid Sydney, a unique public festival to “transform the city into a spectacular living canvas of music and light in and around the Sydney Opera House, The Rocks, Circular Quay and City Centre.” [1]

The beauty of the festival lies not only in the array of different artworks and performances shown during the course of Luminous, but also, according to Eno, in the common denominator of the combined artists: the inability to place them in any obvious category. He stated that “[t]hey are people who work in the new territories, the places in between, the places out at the edges. […] Some of them take old forms and infuse them with new life, and make them new again, and others have invented forms of art that didn’t previously exist.” [2] Thus, Luminous created an outlet for the more ambiguous and less easily placed artworks.

The crowning jewel of the Luminous festival was Eno’s 77 Million Paintings, projected onto the distinctive white sails of the the Sydney Opera House (1973), the architectural landmark and designed by architect Jorn Utzon, designated by UNESCO as a world heritage site in 2007.

Through the use of self-generating software, three hundred images hand-drawn by Eno are randomly cut-up, the pieces rearranged and realigned in an endless variety of ways. The randomness of this rearrangement creates a constantly evolving artwork, with a seemingly infinite number of combinations, hence the title. Accompanying the light show is a specially made soundtrack, interwoven with the projected images, all set to create a “mesmerizing soundscape”. [3]

With 77 Million Paintings, Eno stated he wanted the people watching his work to “surrender to another kind of world,” [4] to embrace their own imagination through this surrender. He said that “[b]y allowing ourselves to let go of the world that we have to be part of every day, and to surrender to another kind of world, we’re allowing imaginative processes to take place.” [5] Art, according to Eno, triggers the imaginative process, and through imagination alone can we cope with the gruesome encounters of everyday life. Imagination enables mankind to survive, even during the hardest of times – such as the economic crisis we have been facing the last year or so. [6]

77 Million Paintings is said to be a “very meditative experience” [7], by chief executive Richard Evans. Using the Sydney Opera House (1973), designed by architect Jorn Utzon as the backdrop for this work of art was not a simple choice either. Evans: “[w]e are not colouring in the opera house, we’re actually kind of taking the art of the opera house and raising it to a different level.” [8] In other words: the iconic white sails of the opera house are not just used as a large projection piece, 77 Million Paintings and the opera house itself cooperate extrinsically in order to create a whole new level of artistic experience.

The ambient, looping quality of the work shares similarities with Eno’s early ambient recordings, including his seminal Music for Airports, 1977, which “was designed to be continuously looped as a sound installation, with the intent to diffuse the tense, anxious atmosphere of an airport terminal.”

Historical precursors to 77 Million Paintings in the domain of visual art include Gyorgy Kepes’ Light Mural for KLM, 1959 (above). Light Mural for KLM was programmed by Kepes as “an immense kinetic mural, in which stencilled shapes in light emulate […] the poetry of a cityscape as seen from an airplane at night. Superimposed over the thousands of tiny points of light are coloured arabesques illuminated at different tempos.” [9] Though Kepes did not have the technology at hand to create a flowing and randomly computer-generated work such as Eno’s, his mural can be seen as a predecessor to Eno’s piece. Both are displayed on large scale public building, using lights and changing light patterns at varying speed intervals to create a mesmerizing illuminated artwork, to be enjoyed by everyone. No doubt, for its time, Light Mural for KLM could also be viewed as a meditative experience, not unlike 77 Million Paintings. There is a undeniably hypnotic experience to watching a large scale light play, be it projected and created through techniques of the 2000s, as in Akira Hasegawa’s Digital Kakejiku or with the light installations of the 1950s, such as Otto Piene’s Light Ballet. Early laser artworks, such as Rockne Krebs Day Passage (1970) also deserve mention in this historical context.

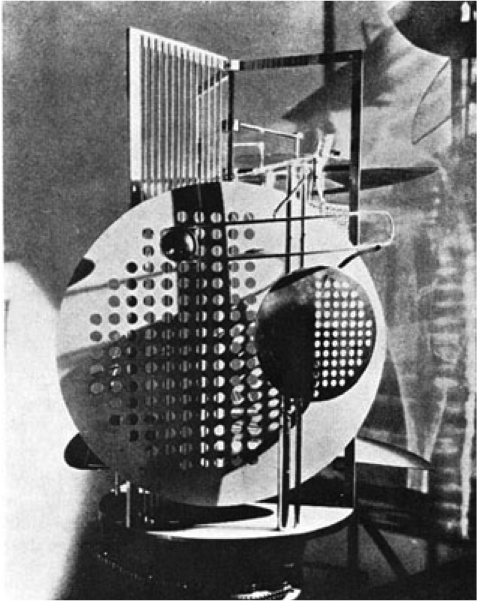

Brian Eno and his 77 Million Paintings are also a contemporary embodiment of Bauhaus master László Maholy-Nagy’s visionary use of artificial light as an art medium, exemplified by his renowned Light Space Modulator or Light Prop (1930, below)). Maholy-Nagy was also an important theorist on the topic, writing in 1928 that,

“Ever since the introduction of the means of producing high-powered, intense artificial light, it has been one of the elemental factors in art creation, though it has not yet been elevated to its legitimate place. The night life of a big city can no longer be imagined without the varied play of electric advertisements, or night air traffic without lighted beacons along the way. The reflectors and neon tubes of advertising signs, the blinking letters of store fronts, the rotating coloured electric bulbs, the broad strip of the electric new bulletin are elements of a new field of expression, which will probably not have to wait much longer for its creative artists.” [10]

With the advent of projection mapping and public screens, the artistic use of light has become an increasingly prevalent mode of production, and creative artists like Eno are expanding the field and contributing to its critical acceptance. On the other side of the spectrum of scale, Eno has also developed a number of applications for smartphones and pads that allow users to interact with generative ambient image and soundscapes, providing an intimate person experience.

Links

Luminous Festival Website no longer operational. Festival now called VIVID

Sources:

[1] [2] Luminous Festival Media Release, March 19, 2009. Retrieved from Luminous Festival website (no longer online) http://luminous.sydneyoperahouse.com.

[3] 77 Million Paintings, found under ‘Installations’ at official Luminous website.

[4] [5] [6] [7] [8] Mail Foreign Service. ‘Sydney Opera House’s white sails turn into giant canvas for spectacular light display’. Daily Mail Online. 26 May 2009. Retrieved from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/worldnews/article-1188229/Sydney-Opera-Houses-white-sails-turn-giant-canvas-spectacular-light-display.html#ixzz0j7Qx2PsQ

[9] Kepes, Gyorgy. Light Mural for KLM. (1959) As found in Shanken, Edward. Art and Electronic Media. London: Phaidon, 2009: pp58

[10] Maholy-Nagy, László. The New Vision. (1928) in Shanken, Edward. Art and Electronic Media. London: Phaidon, 2009: pp 194

[11] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ambient_1:_Music_for_Airports